What is Floating Rate Notes?

Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) are fixed income securities that pay a coupon determined by a reference rate that resets periodically. As the reference rate resets, the payment received is not fixed and fluctuates over time. FRNs are in demand among investors when it is expected that interest rates will increase.

The floating-rate note is, as the name implies, an instrument whose interest rate floats with prevailing market rates. Like Eurodollar deposits, it pays a three—or six-month interest rate set above, at, or below LIBOR. Like international loans, this interest rate is reset every three or six months to a new level based on the prevailing LIBOR level at the reset date.

More precisely, floating-rate notes issued outside of the country of the currency of denomination n are issued in the form of Euro bonds, which makes them in some respects as much a capital-market instrument as a money-market instrument. But the framework we use places pricing at the center of what defines an instrument, and FRNs are priced in part like money-market instruments and in part like conventional fixed-rate bonds.

Table of Contents

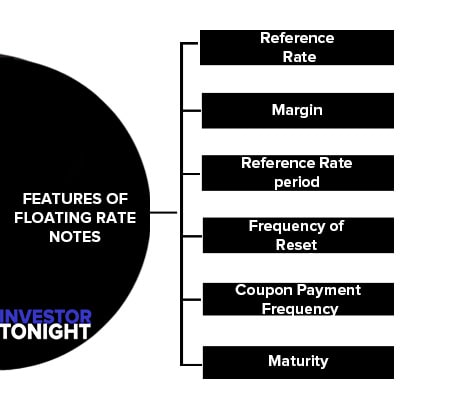

Features of FRN

All floating-rate notes have a coupon that is reset at fixed intervals in accordance with some preset formula, but there are many variations on this theme. Most FRNs can be characterized by the following features:

Reference Rate

The reference rate is the interest rate to which the coupon payment is linked. This is normally a short-term rate, so that some see FRNs as a substitute for money-market instruments. In the Euro markets, the reference rate is usually LIBOR, although a few FRNs have used other reference rate (such as LIBID, LIMEAN, or the U.S.-Treasury-bill rate). The rate is normally reset at the beginning of each coupon period, and interest is paid in arrears.

Margin

The margin is the spread between the coupon payment and LIBOR. A coupon payment on FRNs are generally LIBOR plus (or minus) some fixed amount. This spread reflects the differential risk at the time of issue between investing in the FRN and investing in a bank deposit paying LIBOR.

LIBOR itself is usually about 1/8 percent higher than prime banks’ bid rate in the interbank market, reflecting the risk of the bank with which funds would be deposited, and perhaps a discount for illiquidity. An FRN carries the default risk of the issuer over the life of the note and the liquidity risk of a tradable, but not necessarily traded, security.

Reference Rate period

The reference-rate period is the maturity of the security to which the FRN’s coupon is linked, such as three—or six-month Euro dollar deposits. And FRN coupon is quoted as the LIBOR—period rate and the margin—for example, six-month LIBOR plus 3/16 per cent.

Frequency of Reset

Reset frequency is the period between coupon-reset dates and normally coincides with the reference-rate period.

Coupon Payment Frequency

This is the interval between coupon payments, and normally coincides with the coupon-reset periods.

Maturity

The date on which the principal on an FRN will be redeemed is the maturity date. Many FRNs have call features—that is, the issuer may, at its option, redeem the FRN at certain prespecified dates prior to maturity.

A “plan vanilla” FRN is a fixed-maturity bond whose reference-rate period, frequency to reset, and coupon-payment period are of different lengths. The rate is reset monthly but paid semiannually. The coupon is the arithmet

Pricing FRNS

In some respects, an FRN is like a short-term money-market instrument. The rate on the FRN at issue is set high enough that the note is worth 100. at each reset period, the rate is raised or lowered to match the prevailing market rate.

So, credit-risk changes aside, its price should return to 100, which means you could buy it today (a reset date) and sell it six months later at par, collecting your six-month coupon—just like a Eurodollar CD. Even if the investor made some other assumption about the rollover price (the price at the next reset date), he could use this approach to calculate the money-market return.

This is a somewhat naïve approach the money-market method. It is helpful to those who wish to compare the yield on an FRN held as a short-term investment in lieu of another money-market instrument, and the fact that the rate is reset to market offers some comfort to such investors, but not much: FRNs are medium—or long-term bonds, and their prices at reset dates can deviated, and have deviated, far from par, for reasons associated with general

FRN market conditions as well as the creditworthiness of the specific issue. Thus we can identify three distinct influences on the price of an FRN:

Credit condition of the issuer: The price at the reset date will fall below par if the promised margin relative to LIBOR is perceived as an insufficient reward for an issuer’s deteriorated credit condition. The most direct measure is the issue’s credit rating. A note issued as a AA may be downgraded to A or worse for reasons specific to the issuer.

Market perceptions of FRNs in general: Changes in investors’ perceptions of the FRN market as a whole or of a particular segment of the market may cause a particular issuer’s FRN to trade above or below par on reset dates.

In the early days of the market, many issues were seen as generously priced and trade above 100. then in the late 1980s, the opposite happened. Subordinated bank debt was priced in much the same way as unsubordinated debt until the Bank of England changed its rules concerning the investment by one bank in the debt of another bank.

After the change, the market reassessed the relative risk of subordinated to unsubordinated FRNs. This reassessment resulted in a sharp widening of required margins and a fall in bid prices on subordinated debt relative to unsubordinated debt of the same issuers. The most visible and devastating effect was on the price of perpetual FRNs.

Money-market rate: The FRN price will be affected by changes in short-term rates—specifically, the level of LIBOR between now and the next coupon reset date. A change in this rate will change the FRN’s valued as if it were a money-market instrument maturing on the reset date.

The method used for pricing and comparing FRNS reflects the fact that they are, in some respects, bond instruments and, in some respects, money-market instruments. When comparing two straight bonds, the standard approach is to consider the yield to maturity of each bond and the liquidity and credit risk of the bonds.

They yield is sometimes expressed as a spread over “ benchmark” U.S. treasury yields, but because the FRN’s coupon rate fluctuates, the standard yield measures are useless. From this reason, and because so many FRNs are held by those seeking a spread over their short-term cost of funds, the market has developed a measure of an FRNs effective spread over LIBOR: To get the effective spread over the instrument’s remaining life.

We adjust the quoted margin by amortising the premium or discount at which the FRN is trading. The discount-margin approach is the industry standard for comparing FRN spreads.

Discount Margin and the Neutral Price

The discount margin is a measure of the effective spread, relative to LIBOR, that an investor would earn if he bought the FRN at some price today and held it to maturity.

It is the margin relative to LIBOR that is necessary to discount the cash flows from an FRN so that the sum of the present value of the flows is equal to the gross price of the note. It is calculated in a manner similar to the yield to maturity of a fixed-rate bond.

Because the coupon stream is uncertain, it is necessary to make some assumption about average LIBOR from the next coupon date until maturity, although fortunately, the discount margin is not very sensitive to the assumption made.

Naturally, nobody can be sure what rates will prevail over the life of the FRN, but one acceptable method is to use the implied forward rate for the remaining life fro the yield curve for is preferable because, an FRN can be converted into the equivalent of a fixed-rate instruments. Better still, use the swap yield curve: this is preferable because, an FRN can be converted into the equivalent of a fixed-rate bond using an interest-rate swap.

Caps, Floors, Calls and Puts in FRNs

Many floating-rate notes have option features. Most, in fact, have a minimum coupon level; this is called a floor. Some have a maximum coupon level, called a cap. An FRN that has both a floor and a cap is said to be collared.

From the investor’s viewpoint, buying a floored FRN may be regarded as purchasing a plain FRN plus a strip of European call options on LIBOR with strike prices equal to the floor level minus the margin. On each coupon date, the investor receives LIBOR plus the margin, plus the intrinsic value of the option, if any.

A “cap floater” may be considered as an uncapped FRN, plus a strip of European puts on LIBOR that the investor has sold, with a strike price equal to the cap level minus the margin. The number of puts equals the number of reset periods in the note’s remaining life. The investor is paid in the form of a higher stated margin or a lower price than plain-vanilla FRNs—in other words, with a higher discounted margin.

Read More Articles

- What is Financial Management?

- What is Financial Statements?

- What is Financial Statement Analysis?

- What is Ratio Analysis?

- What is Funds Flow Statement?

- What is Cash Flow Statement?

- What is Working Capital?

- What is Cost of Capital?

- What is Capital Budgeting?

- What is Dividend Policy?

- What is Cash Management?

- What is Depository?

- What is Insurance?

- What is Financial System?

- International Financial Reporting Standards

- Stability of Dividends

- What is Factoring?

- Determinants of Working Capital

- Public Finance

- Public Expenditure

- What is Public Debt?

- Classification of Public Debt

- Federal Finance

- Effect of Public Debt

- Expenditure Cycle